It’s nearly 3:30 a.m. on June 19, 2018, and inside a room at the Delta Armouries Hotel in London, Ontario, a six-second cellphone video is being recorded.

“You’re OK with this?” an unidentified man asks a young woman, who is shown from the neck up. “I’m OK with this,” she responds before the video cuts off.

Almost an hour later, another cellphone video is recorded. This one is about 12 seconds long. The same woman stands with a towel covering her chest.

She asks, “Are you recording me?” before declaring, “It was all consensual. You are so paranoid, holy. I enjoyed it, it was fine. It was all consensual. I am so sober, that’s why I can’t do this right now.”

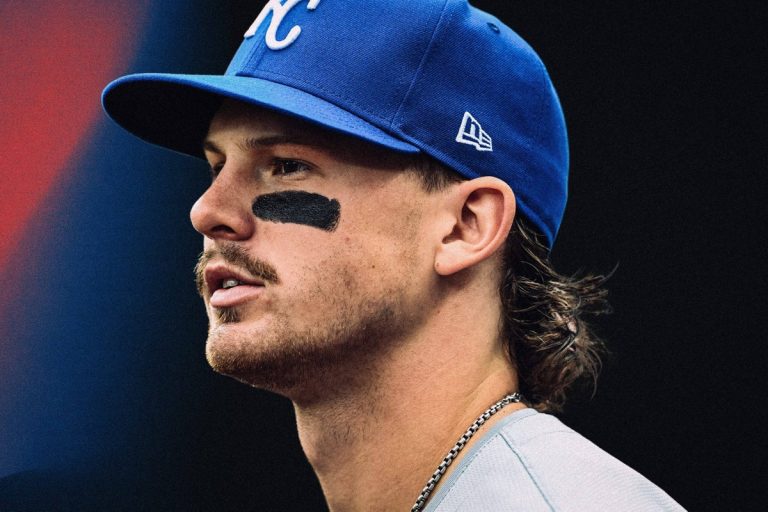

This week, almost seven years since those two brief videos were recorded — and first reported on by The Globe and Mail and TSN — those 18 seconds of footage will be at the center of a case that has grabbed the attention of the hockey world as five former members of Canada’s 2018 gold medal-winning World Junior Championship team — Alex Formenton, Carter Hart, Dillon Dubé, Michael McLeod and Cal Foote — each face one count of sexual assault, and McLeod a second charge for “being party to the offense.”

In a lawsuit filed by the woman — referred to as E.M. in court documents — she said that eight players assaulted her over several hours in the London hotel room. She confirmed she engaged in consensual sex with one player, but he invited several of his teammates into the hotel room without her knowledge or consent. E.M. maintains she did not consent to any of the sexual contact or acts that followed. She also noted several of the players had golf clubs in the room, and that she felt physically intimidated and unable to leave.

The defendants, now aged 25 to 27, came of age during a turbulent period of prominent revelations of sexual violence by formerly esteemed figures. For many athletes from that era, a perception emerged that they were targets due to their fame and/or wealth and that steps and strategies had to be adopted to head off false allegations. In response, athletes sought digital indemnifiers. From “sex contracts” to strategic sexting to so-called “consent videos,” more and more athletes are creating digital footprints of their sexual encounters.

“There’s been a series of events, or cascade of things, leading to cultural change … this mindset or sentiment among some who fear accusations because they think that false accusations are common,” said Kristen Jozkowski, a sexual violence expert and researcher at Indiana University in Bloomington.

In 2003, long before the Me Too movement brought widespread awareness to the issues of consent and sexual assault, Los Angeles Lakers star Kobe Bryant was accused of raping a 19-year-old hotel employee in Edwards, Colo.

The case garnered widespread media attention and dominated headlines. The case did little to impede Bryant’s basketball career, while the woman’s sexual history was paraded in court and across tabloids.

“The criminal justice system is not designed to protect women in these types of situations, especially with athletes,” said Dan Gilleon, a San Diego attorney who represented a 17-year-old girl who alleged she was gang raped by three San Diego State football players in 2021. (All cases, but one, have been settled.)

The criminal case against Bryant was ultimately dropped after the complainant refused to testify, but Bryant settled the woman’s civil suit for an estimated $2.5 million.

The aftershocks of that scandal on the lives of athletes were significant. Some turned to “pre-sex agreement forms” as insurance against any allegations. In an interview with Sports Illustrated in 2003, Ava Cadell, an L.A. area sex therapist, said in the wake of the Bryant case she had begun drawing up such agreements. “Athletes are going to carry consent forms just like they carry condoms,” she said. “It’s another layer of protection.”

Stephen Jackson, who played 14 seasons in the NBA, explained to SI why he would rely on a consent form before sex: “People look at us as targets and try to get what they can out of us.”

The concern amongst professional athletes spread to college campuses when, in 2006, an exotic dancer hired to perform at a team party accused three members of the Duke University men’s lacrosse team of raping her. The details were splashed across front pages; “60 Minutes” devoted five separate segments to coverage of the case. Yet, it would later be revealed that the assault accusation against the trio was a fabrication. A “Tragic Rush to Accuse” read a headline in the Canadian National Post.

In 2009, Apple unveiled its iPhone 3GS, the first model with both photo and video recording capabilities. Visual evidence of sexual encounters became more ubiquitous, in the form of both agreed-upon sex tapes and secret voyeuristic recordings. In 2013, Roxanne Jones, former vice president of ESPN, penned an op-ed for CNN titled “Young men, get a ‘yes’ text before sex.’”

“I’ve actually been encouraging my son and his friends to use sexting — minus the lewd photos — to protect themselves from being wrongly accused of rape,” Jones wrote about her college-aged son. “Because just as damning text messages and Facebook posts helped convict the high schoolers in Steubenville of rape, technology can also be used to prove innocence.”

Said Jozkowski: “There’s at least over 10 years of initiatives, as well as individuals who have sort of attempted to implement this kind of technique of ‘I’m going to record a video on my phone. … I’m going to record you saying you’re consenting and I’m consenting, and then we have this sort of record to verify our consent. That way, neither of us can say rape later on.’”

As the London Five entered their teenage years and climbed the rungs of junior hockey, there were numerous publicized cases where athletes were accused of sexual assault and visual evidence was key to the defense.

In 2012, three teenage members of the Ontario Hockey League’s Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds — Nick Cousins, Andrew Fritsch and Mark Petaccio — were charged with sexual assault of a woman. But a series of intimate photographs, which depicted the woman participating in a sexual act with more than one male present, ultimately torpedoed the case, according to Sean Sparling, who spent 18 years in Sault Ste. Marie police service’s major crimes unit.

“Even if she didn’t want it to happen, the photograph raised the issue of whether you could prove lack of consent,” recalled former Sault Ste. Marie Crown Attorney Bill Johnson.

Commenting on the allegations against Cousins, Philadelphia Flyers director of player development Ian Laperriere later told the Philadelphia Daily News: “Let’s be honest, stuff like that has been happening forever. You can’t get away with anything now. He can’t put himself in those situations.”

In 2014 and 2015, at a time when most of the London Five were making their OHL or WHL debuts, the troubling culture of elite-level youth hockey was laid bare:

In 2014, a group of four Olympiques players allegedly sexually assaulted a woman in a Quebec City hotel room, and there was also a complaint of “gross indecency” involving six players from the same team and an intoxicated woman in the washroom of a pizzeria. Also that year, the University of Ottawa suspended its men’s hockey team for an alleged gang rape.

Around the same time, a vulgar online handbook of sorts, known as “The Junior Hockey Bible,” circulated in youth hockey circles.

While some of the 84 entries refer to lingo used on the ice against opponents, most of the definitions are for words used to describe women, specific sexual acts to be performed on them, or ways to protect yourself from them.

The now-defunct document, which Vice called a “sexual assault guide book,” defines “Swamp Donkey” as a type of woman who “must be avoided before the consumption of at least 13 beers, and after that precede (sic) with caution and only poke her if you can degrade her in some way in front on the boys, preferably on video camera.”

Or “Kangaroo Court,” “the law of the dressing room … enforced on players who commit crimes with disgusting sluts of the opposite sex.” Other players will make fun of this individual, but “credit can be given for pretty much anything that degrades the broad in any way. Extra points for anything filmed on camera.”

While there are several references to recording these encounters, there are also warnings, too: “You may videotape if possible, but do not make copies. Evidence can be harmful.”

In 2015, the Quebec Maritimes Junior Hockey League began teaching “Unsafe Sexual Behavior” to its players, according to court records. On a training slide titled “the meaning of consent,” the two following recommendations are provided to athletes: “A person accused of sexual assault can argue in court that he honestly believed his partner agreed to the sexual activity. This defense is referred to as an ‘honest but mistaken belief in consent,’” and “Do not share information that could incriminate anyone.”

The Me Too movement arrived in 2017 — a year before the alleged sexual assault in London. It created greater awareness of sexual violence and calcified concerns amongst some men’s groups, leading to more reliance on “documented consent.”

In 2023, two former Ohio State football players were acquitted on rape and kidnapping charges based on a “consent video,” in which a naked, crying woman states the encounter was consensual. The defense attorney for one of the players said his client took the video after receiving instructions by a school official at an OSU football team meeting to “always make sure you get it on record that whatever you do is consensual.”

Last year, in Hamilton, Ontario, less than 100 miles from London, Jack Densmore, a popular YouTuber known for his controversial videos, testified that athletes, celebrities, and others he partied with advised him to make consent videos, so he adopted the practice himself. But at his own sexual assault trial in 2024, it was determined he had taken a video of a woman without her permission in what he later claimed was an effort to create a record of consent. He was sentenced to three years in prison.

Densmore’s case underscores the misunderstanding that experts say surrounds consent in general and the effort to capture it digitally. Consent can be given and taken away, and may change over the course of an interaction. And jurors who may be viewing those 18 seconds of footage of E.M. during the Hockey Canada trial in London may have to consider that and more.

“The video may be misleading. It may include a component of a larger interaction. It may be potentially coerced,” said Jozkowski. “Someone can look a particular way, do a particular thing, and then a moment later, the video is off and they are screaming ‘no.’”

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic. Images: iStock)