Museum of the Bible Returns Ancient Gospel Looted From Greek Monastery

The Museum of the Bible in Washington, which has been working to regain credibility by giving back tainted objects in its collection, returned a handwritten gospel that is more than a thousand years old to the Greek Orthodox Church on Tuesday afternoon after determining that it had been looted from a Greek monastery during World War I.

The museum said that it transferred the artifact, which its founders acquired at a Christie’s auction in 2011, to an Eastern Orthodox Church official in a private ceremony in New York. The manuscript is to be repatriated next month to the Kosinitza Monastery in northern Greece, where it had been used in liturgical services for hundreds of years before it was stolen by Bulgarian forces in 1917.

The return was in line with the Museum of the Bible’s policy in recent years of investigating the provenance of its entire collection after early acquisitions by its founders, the owners of the Hobby Lobby craft store chain, were found to include thousands of items looted from ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. The company paid $3 million in 2017 to settle claims with the U.S. government over not exercising due diligence in a chaotic, multimillion-dollar international antiquities buying spree beginning in 2009.

The Greek Orthodox Church has said that several other American institutions wound up with artifacts looted from the same monastery.

The Museum of the Bible’s website traces the manuscript’s history and the chain of ownership, from its creation in the late 10th- or early 11th century, through the looting of the monastery in 1917, through various sales after the war ended. It was resold at auction in the United States in 1958, and more recently by Christie’s in 2011.

“Certainly the marketplace has its challenges,” said Jeffrey Kloha, the Museum of the Bible’s chief curatorial officer, who was brought in after the problematic acquisitions. “Things have been moving in the market for some time, and in some cases decades, that have origins that are not legal.”

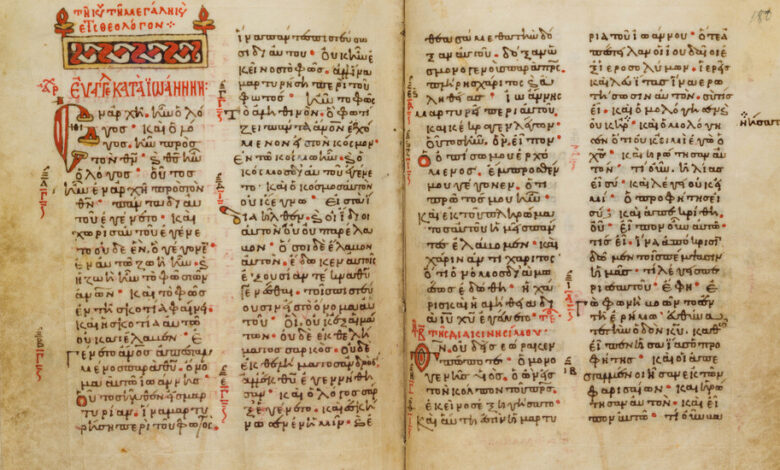

The manuscript, some of its pages darkened by the smoke from candlelit prayers and others smudged over centuries by monks turning the pages, was among a library of over 400 manuscripts carted off by mules by Bulgarian forces who stormed the monastery in 1917.

“It’s definitely an object that was used,” Kloha said. “It would have been part of monastic life on a regular basis.”

The Museum of the Bible, which opened its doors in 2017, has not publicly displayed the manuscript because of questions over provenance; the manuscript was included in a traveling exhibition at the Vatican in 2012.

“I think the Museum of the Bible is a great example of how not to build a collection, but I do wish other American museums would follow its example when dealing with their own existing problematic collections,” said Tess Davis, executive director of the Antiquities Coalition, which aims to combating the illicit trade in antiquities. “In this case, curators saw red flags, they followed where they led, realized the manuscript was stolen, reached out to its rightful owners and voluntarily returned it.”

Kloha said he hoped his museum’s return of the manuscript would encourage other institutions to return manuscripts from the monastery found to have been looted during World War I.

The Greek Orthodox Church sued Princeton University four years ago to try to recover four manuscripts many scholars believe were looted from the same monastery. The case has not been resolved. Princeton did not immediately respond to a request for comment, but in 2018 it said that it did not believe the manuscripts had been looted.

In 2015, the church asked for the return of other manuscripts believed to have been looted from the same monastery that were held by Duke University, the Morgan Library and the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago. The theology school returned the manuscripts it was holding in 2016.

Davis, from the Antiquities Coalition, said there was an inherent risk in buying religious artifacts, which are almost always intended to remain for use within the religious community.

“There are surprisingly few legal sources of sacred art on the market,” she said. “It serves as yet another warning of the risk of buying ancient art and artifacts.” Davis said most religious antiquities were looted from archaeological sites or graves, or stolen from religious institutions.

She said that recent repatriations of artworks — including France’s decision to return objects to Benin and the return on Cambodian artifacts after an investigation by the U.S. government — illustrated the risks of buying artifacts of uncertain provenance.

“It’s not just individuals or amateurs who are getting in trouble and making mistakes,” she said. “It’s the top auction houses, it’s the top museums, it’s the top collectors.”

Kloha said that his museum had cut back dramatically on its acquisitions, and put in far more rigorous safeguards.

“The procedures in place now are very, very tight,” he said. “If we don’t have every detail filled in, it’s simply not considered. The process is very different than it was 10 years ago.”