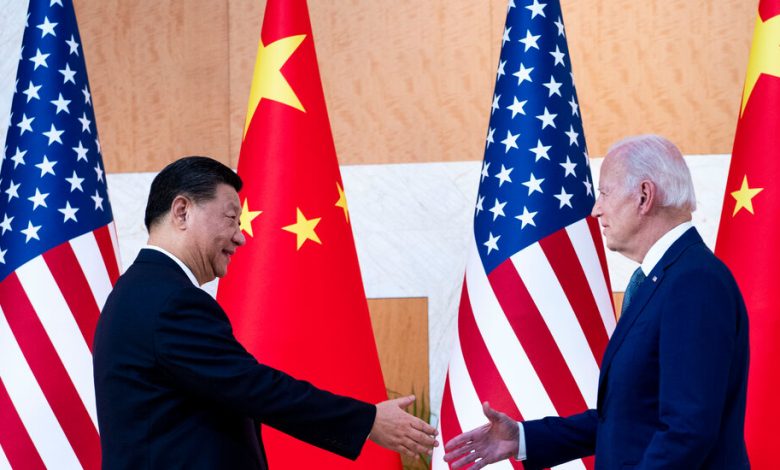

Distrust Has Shaken the U.S.-China Relationship

This article is from a special report on the Athens Democracy Forum, which gathered experts last week in the Greek capital to discuss global issues.

Moderator: Roger Cohen, Paris bureau chief, The New York Times, and host of the Athens Democracy Forum

Participants: Thomas L. Friedman, foreign affairs columnist, The New York Times (appearing virtually); Keyu Jin, author and professor of economics, London School of Economics; and Dingxin Zhao, Max Palevsky professor emeritus of sociology, University of Chicago and department of sociology, Zhejiang University

Excerpts from the panel China vs. the United States — Toward Coexistence or War have been edited and condensed.

ROGER COHEN Hello and good morning to everyone. Nice to see you all.

I’m here with my esteemed panelists to discuss a minor question of the 21st century, which might in fact determine the course of the century: What is the relationship between the United States, which has been the world’s No. 1 since World War II ended, and China, the world’s great rising power?

If I could perhaps start with you, Keyu.As I said, the United States has been No. 1 for a long time and rarely in history have we seen a peaceful transition to dominance in global power, and that is what we’re looking at potentially right now. Do you think that China and the United States with their intense rivalry can avoid war at some point and how?

KEYU JIN First of all, I think they’re not irreconcilable differences between the two powers, but more the problem stems from a lack of effective communication, misunderstanding and, most importantly, a lack of trust that has grown. And, yes, fundamentally there is competition and potentially rivalry. But that does not get the two countries to war.

If you have followed what the premier of China has said — and that really represents what the Chinese people feel that he said — China will not tolerate chaos and instability in the region, and we underestimate how important peace is for the Chinese people, who have gone through huge vicissitudes. Understand that currently, there’s still the goal for the families to educate their kids, buy an apartment in the city, and peace is the fundamental condition to deliver that.

COHEN So why then has [President] Xi Jinping made so many threatening noises about Taiwan, and why have there been provocative military maneuvers around Taiwan? If peace is the goal, isn’t that dangerous?

JIN Well, let’s not forget about the Monroe Doctrine, where the rising power ousted European powers from its continent, so I think it is true that China is going to assert more power in the region along with the regionalization of trade and so forth, but I think strategic ambiguity is also a Chinese method to raise awareness that these provocations can lead to potentially miscalculations, and therefore both sides need to take the temperature down.

COHEN Tom, you were in China and Taiwan earlier this year, and you wrote quite extensively about the lack of trust, which is something Keyujust alluded to, but in spite of it all trade between the U.S. and China hit a record last year and no two global antagonists have ever been so intertwined. What do you think that means for the relationship, which as you’ve written, is plagued by this mistrust. I mean, the U.S. bought $40 billion of Chinese toys, games and sports equipment last year. Given that level, given the level to which the countries are linked, how dangerous is the relationship really?

THOMAS L. FRIEDMAN Well, you know there’s always the chance, Roger, for an accident, but my general view is that the U.S. and China are doomed to compete, and they’re doomed to get along ultimately. Now, that doesn’t mean there can’t be any, say, accidents, but I think at the end of the day there is just an overwhelming interest in both capitals to find a way to work things out. I do think, though, that there has been a shift in the quality of the relationship that has come about over the last decade or so, and that’s unfortunate.

I do believe that it’s not a shift that began in America but came about basically because of a change in power in Beijing. China was on a pretty clear trajectory since 1978 — two steps forward, one step back — of integrating closer and closer with the world and being a little more open every year. Anyone who’s visited China over that period has experienced that.

I had the joy and pleasure of doing bookstore events in China in the late ’80s and early ’90s. It’s one of my biggest book markets. But China is a more closed place today. I think there’s no question President Xi felt that openness — some of the corruption that came with it — was threatening the power and stability of China, the power of the Communist Party, and he decided he was willing to trade some level of economic growth and integration with the world for a greater level of control. But I don’t think that has to lead to war between our two countries or that it will, and so I think at the end of the day we are, as I said, we’re doomed to figure out a way to live with each other.

COHEN What do you think of the Biden administration’s policy toward China, this determined effort to check China, to view it as a rival, to limit certain forms of investment — semiconductors, etc. Has it been the right policy? Has it gone too far? Has it been too confrontational? I live in France, and President [Emmanuel] Macron believes it’s too confrontational, and that we risk losing China to Russia is a line you often hear in Paris.

FRIEDMAN Yeah, you know I’m in the camp, Roger, of let’s build bridges where possible and draw red lines where necessary. I have written over the last few years of columns that would fall in the category of “Could somebody tell me exactly where this is going?”

COHEN [laughing]: Well, if you don’t know, Tom, how is anyone else supposed to know?

FRIEDMAN What I would simply say is that I think some in the administration have asked that, and I think what you’ve seen in the last three months with a number of high-level trips by Biden administration economic officials — Gina Raimondo, the commerce secretary; and the secretary of the Treasury [Janet Yellen] — there’s been a kind of pulling back a little bit and a desire, I think, to see if we can re-center the relationship a little better.

As I say, a lot of this was an inevitable outcome of the fact that we’ve entered a very different world economically, where trust becomes so much more important when you’re involved in, say, building a global supply chain for chips.

These are incredibly intimate relationships that require a lot of trust, and when you enter a world where everything is dual use — from your TikTok to your refrigerator, anything that is connected — then trust becomes the coin of the realm. I think China’s got to adjust to that.

I think both sides should be asking themselves some really important questions. I think the question China should be asking about the future of this relationship is how was it that we, China, had the most powerful, the most influential lobby in Washington, called the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the U.S. China Business Council. I mean, the American business community that did business with China was an incredibly powerful lobby and source of ballast in the relationship between these two countries, and China lost that lobby.

That wasn’t something the administration ordered. These were people who decided for the very commercial reasons that kept them putting pressure on the U.S. government to maintain an open and nonconfrontational relationship with China. China lost that because too many companies felt that China was not playing by the rules.

At the same time, you know America has so benefited from the inflow of Chinese students and Chinese professors who have enriched our universities and our companies, and we need to be asking ourselves some very tough questions: What are we doing, what are we saying when so many of these people are starting to say, “I don’t think I want to make my future here. I’m afraid to make my future here.” So I believe that we’re doomed to figure this out. We’re in that kind of situation of tugging back and forth as we go.