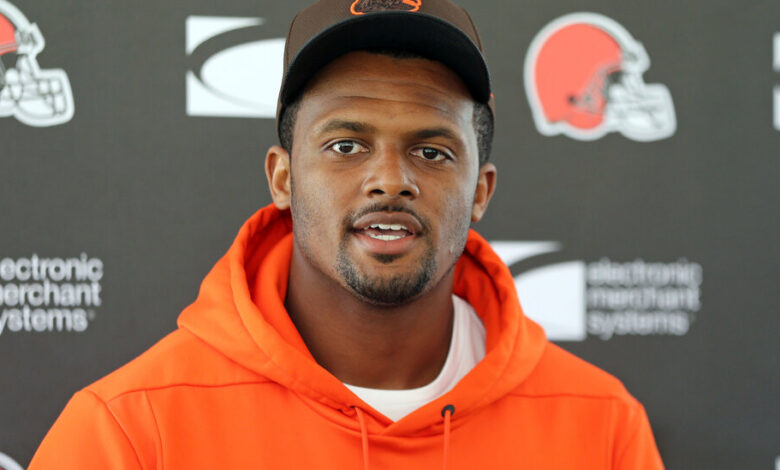

Deshaun Watson’s Apology Undercuts the N.F.L.’s Message

When Roger Goodell became N.F.L. commissioner in 2006, he made it clear that one of his biggest priorities would be to police players whose actions might tarnish the league’s carefully crafted image.

In the decade and a half since, Goodell has leaned heavily on a player’s contrition when determining what penalties to assess. As a rule of thumb, players who apologized and promised to learn from their mistakes have been treated more lightly than those who refused to sincerely own up to their wrongdoing.

But Goodell’s search for remorse has obvious limits, as the settlement with Cleveland Browns quarterback Deshaun Watson once again showed. On Thursday, the league said that Watson would be suspended for 11 games and pay a record $5 million fine after more than two dozen women accused him of sexual misconduct in massage appointments.

The league had previously argued that Watson deserved to be suspended indefinitely, in part because he refused to apologize for his actions, something that unnerved advocates for victims of sexual abuse as well as one woman who has not settled with the quarterback. Indeed, Watson insisted numerous times that he did nothing wrong.

With the threat of more severe penalties looming, Watson finally issued an apology last Friday.

“I want to say that I am truly sorry to all of the women that I have impacted in this situation,” Watson said in an interview with the Browns broadcast team. “The decisions that I made in my life that put me in this position, I would definitely like to have back, but I want to continue to move forward and grow and learn and show that I am a true person of character.”

In signing off on the settlement, Goodell seemed to think that apology was sufficient.

“Deshaun has committed to doing the hard work on himself that is necessary for his return to the N.F.L.,” Goodell said in his statement announcing the settlement.

Watson issued his own written statement expressing remorse, but it was quickly overshadowed by his own, more candid words minutes later.

“I’ve always stood on my innocence and always said I’ve never assaulted anyone or disrespected anyone, and I’m continuing to stand on that,” he said after a reporter asked why he accepted the suspension and fine after long insisting he had done nothing wrong.

The episode raised fresh questions about the utility of Goodell’s extracting of apologies from players accused of wrongdoing. While showing remorse can signal that a player recognizes the need to change his behavior, an apology can also help the league manage the crisis publicly.

“There might be many other motivations for asking for an apology, including that it’s good public relations,” saidJodi Balsam, who was a lawyer at the N.F.L. and now teaches at Brooklyn Law School.

But if a player cannot even apologize sincerely, there is little hope that he will absorb any of the lessons of treatment.

“One thing that anyone who’s been in therapy knows is, if you don’t think you need help, counseling is a complete waste of time,” Deborah Epstein, the co-director of the Domestic Violence Clinic at the Georgetown University Law Center, said. “For Goodell to trumpet the penalty makes no sense if Watson is going to disclaim any responsibility.”

Epstein advised the N.F.L. Players Association on domestic violence after video showing Baltimore Ravens running back Ray Rice knocking out his fiancée was published in 2014. But Epstein left that role in frustration because, she said, the league and union were more interested in protecting players than in truly grappling with the profound problem of violence against women.

Epstein’s hunch was confirmed in March when numerous teams scrambled to trade for Watson once it was clear he would not face criminal charges. The Browns ultimately won that bidding war, and the team’s owners, Jimmy and Dee Haslam, have covered for Watson, proclaiming that he was remorseful when he said clearly that he was not.

The Haslams stood next to Watson as he repeated his innocence, then said the quiet part out loud: Watson’s behavior should be minimized because he’s a talented athlete.

“Is he never supposed to play again? Is he never supposed to be part of society?” Jimmy Haslam said. “I think it’s important to remember, Deshaun is 26 years old, OK, and is a high level N.F.L. quarterback, and we’re planning on him being our quarterback for a long time.”

Balsam said that the owners, in their rush to sign Watson, undermined Goodell’s pursuit of an indefinite suspension, and until that dynamic changes, the league will be constrained in its discipline of players.

“There has to be a change of heart by the owners, but they’re always looking over their shoulders that someone else will get bargain basement talent,” she said. “There’s a lot of mixed messages, and I don’t blame the victims for being disturbed.”

One of the accusers continues to be disturbed. While 23 of 24 women have settled their cases against Watson, Lauren Baxley has held out because she said Watson had not sufficiently acknowledged what he was accused of doing.

“I have rejected all settlement offers, in part because they have not included any sincere acknowledgment of remorse and wrongdoings, nor have they included any promises of rehabilitative treatment,” Baxley wrote on the Daily Beast website.

Even the best trained experts cannot know with certainty whether an apology is sincere. What they look for, though, are actions that back up an apology, like commitment to treatment programs.

“I don’t know how you X-ray into someone’s soul,” said Judy Harris Kluger, a former prosecutor who ran a sex crimes unit and is now the executive director of Sanctuary for Families, a group that helps victims of domestic violence. “It’s the person’s actions that tell you whether they are contrite or apologetic. But here, it’s the opposite.”

Jenny Vrentas contributed reporting.